Webinar Series | Sommer 2022

Check out all webinars from the Trends vs. Hypes in AFM series here.

L.M. Eng 1,2

1 Institute of Applied Physics, TU Dresden, Dresden, Germany

2 ct.qmat: Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence - EXC 2147, TU Dresden, Germany

Magnetic Force Microscopy (MFM) is a well-known non-contact scanning probe (SPM) technique established for more than 35 years by now, that is capable of mapping near-surface magnetic textures and structures down to the 10-nm-spatial resolution. MFM becomes an indispensable and complementary tool in modern-type material analysis, especially when focusing for instance on topological and low-dimensional systems.

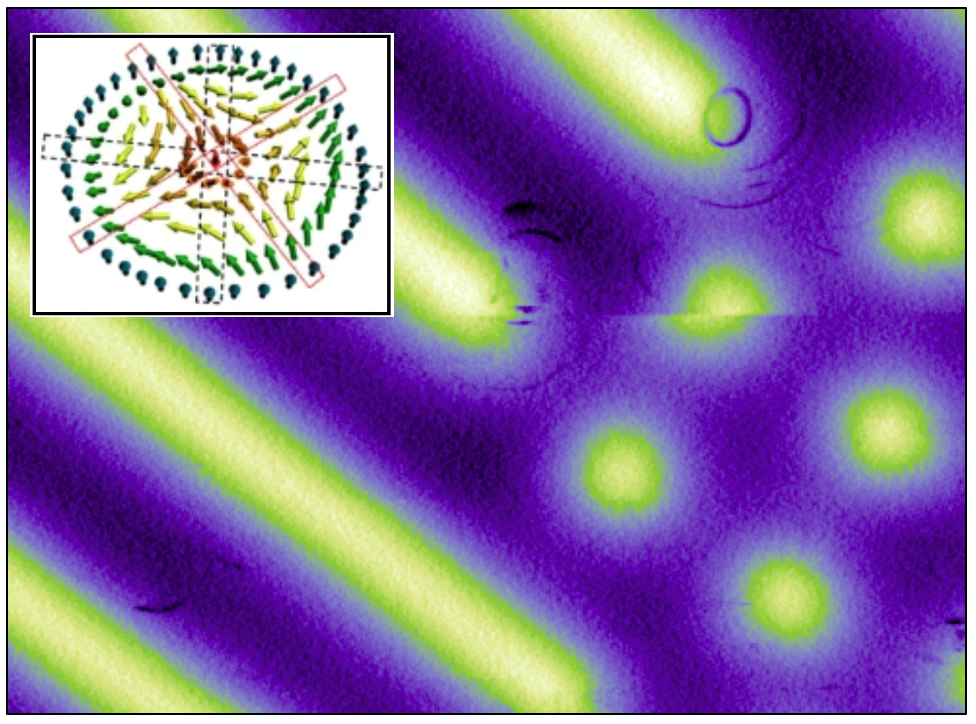

In this webinar, I will focus on how we can separate magnetic information by MFM, from other (local) signals, especially also shedding light on the different SPM “channels” that might deliver the wanted magnetic information, i.e. as a frequency shift, as a net dissipation signal, or even as an electrostatic signal, just to mention the most popular ones. Careful analysis of these signals even allows to differentiate Néel-type from Bloch-type domain walls (DWs) [1], hence paving the way for the quantitative investigation of magnetic skyrmions (SKYs) [2-10] and antiskyrmions [11-13]. I will finish this webinar by emphasizing on the indispensable need of MFM for the nanosciences, in that MFM has the power to readily prove that many estimates on magnetic textures, deduced from macroscopic measurements such as Anomalous and Topological Hall transport, are in fact wrong and heavily overinterpreted [14].

References:

[1] R. Streubel et al., Phys. Rev. B 87, 054410 (2013); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.054410.

[2] P. Milde et al., Science 340, 1076 (2013); https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1234657.

[3] I. Kézsmárki et al., Nat. Mater. 14, 1116 (2015); https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4402.

[4] P. Milde et al., Phys. Rev. B 100, 024408 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.024408.

[5] P. Milde et al., Phys. Rev. B 102, 024426 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.024426.

[7] P. Milde et al., NanoLett. 16, 5612 (2016); https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02167.

[8] A. Butykai et al., Sci. Rep. 7, 44663 (2017); https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44663.

[9] K. Geirhos et al., npj Quantum Materials 5, 44 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-0247-z.

[10] E. Neuber et al., J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 30, 445402 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aae448.

[11] B.E. Zuniga Cespedes et al., Phys. Rev. B 103, 184411 (2021); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.103.184411.

[12] A.S. Sukhanov et al., Phys. Rev. B 102, 174447 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.174447.

[13] B.E. Zuniga Cespedes et al., Parksystems App. Note #71 (2021); https://parksystems.com/medias/nano-academy/articles/2405-mfm-on-mn1-4ptsn-investigating-magnetic-hosts-for-anti-skyrmions.

[14] G. Malsch et al., ACS Appl. Nanomater. 3, 1182 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.9b01918.

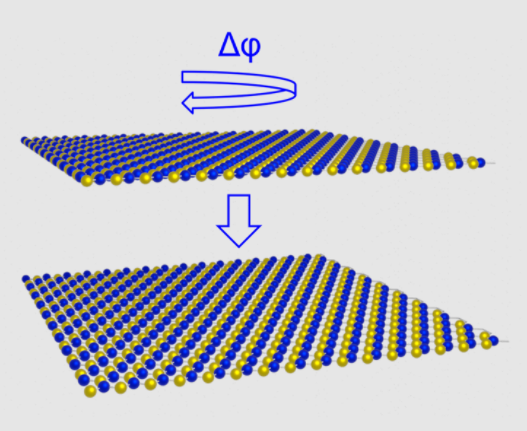

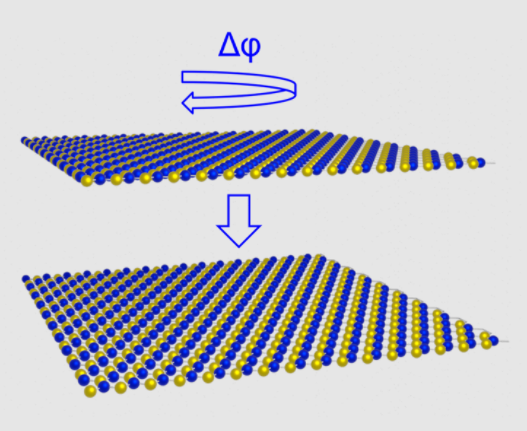

A schematic of the formation of parallel stacked bilayer hBN is shown in addition to a contact potential difference map measured using sideband KPFM.

Image caption

Image caption

Image caption

CHAIR IN EXPERIMENTAL PHYSICS / PHOTOPHYSICS

In the group of Professor Lukas M. Eng characterization on the nanometer-scale is combined with sophisticated materials science, spanning multiple research areas such as photo-physics, nano-optics, plasmonics, scanning probe microscopy and materials science.